When the Knife Hand Fails

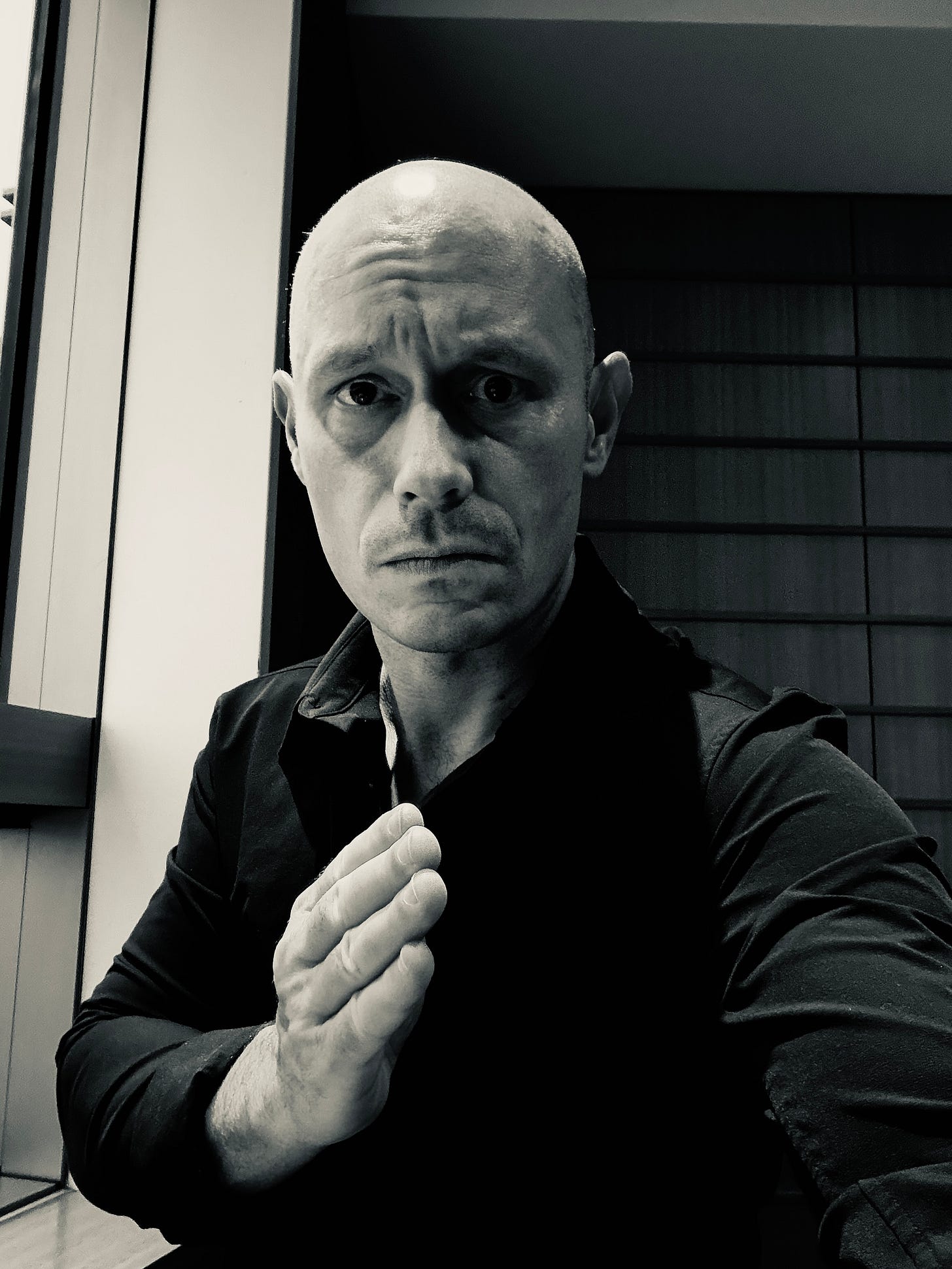

If you have ever served in the US military, you undoubtedly know this look: stern eyes, firm jaw, and the knife hand.

To those who have not, you’re probably thinking, “what the hell is this?”

Well, this is a method used in the military to communicate direction or corrective action directly, with precision and clarity. When life or property are at stake, the knife hand comes out to accentuate a narrative, point clearly at an objective, and serve as an exclamation point.

Since leaving the military nearly twenty years ago, I have holstered the knife hand (apparently, contrary to what the military would lead you to believe, pockets do serve a purpose). But I have found the technique of clear, concise, and direct communication useful when time is of the essence or there is no room for negotiation or misinterpretation. When executed with calm and rational precision, the technique is effective.

That is, until it’s not.

When communicating with individuals in North America and across Europe, the “professional knife hand” is typically well received, especially in places like the Nordics and Germany where clarity and precision are highly valued. In Latin and South America, as well as in some states in the US, I’ve found that the technique works well only after rapport and trust have been established, whereas in places like Boston and New York, my tactfully direct style is viewed as perfectly normal.

Recently, however, I ran into some trouble and inadvertently caused embarrassment to a colleague of mine in Asia. Each culture has its own unique patterns for decision making, exercising influence, and offering direction. If you want to learn more, I recommend Kiss, Bow, or Shake Hands by Terri Morrison. I’ve found a professional edge through dedicated study and mastery of the preferred communication patterns of customers and partners in different parts of the world.

Where I failed was while sitting in the comfort of the US, offering clarity and direction to a colleague from another part of the world. Needing to quickly course-correct, I forgot about cultural nuance and brought out the professional knife hand.

In alignment with proper knife hand execution, I proceeded with professional and calm precision until my point was made crystal clear. By the time I was done, I knew I had screwed up.

No matter who you are or how experienced you are, you will make mistakes. What matters more than the mistake itself is how you recover once it’s been made. Recognizing how I made the other person feel, I snapped back into a culturally appropriate posture, humbled myself, and clarified my intent. Even with that, it took weeks of consistent, culturally aware communication to restore our productive rhythm, and truthfully, I still feel awful about it.

With leadership and influence comes responsibility, not only for outcomes, but also for leading from the front. When working with an international team, leading in a style that is well received by the various cultures of your teammates adds another axis of complexity.

I share this story because the greatest tragedy from any mistake is failing to learn from it and missing the opportunity to help others learn from it too.

So, if you work with an international team or travel internationally, I encourage you to take a few minutes to understand the cultural norms and communication styles of those you’ll be working with.

Though the knife hand is undeniably effective, it must be used with caution. You’ll likely get the result you’re after, but you may lose the relationship.

Be well.